Power and puerility

A city is divided as SoCal sports teams choose between courage and cowardice

Father’s Day weekend is one that sports fan often circle. The USGA always lines up the U.S. Open to end this Sunday, which sometimes features the champion clutching the trophy and posing with his recently born infant. The Stanley Cup and NBA Finals are typically nearing their respective conclusions. And the MLB, MLS, and NWSL seasons offer a variety of options for fans who want to be outdoors with their dads as the summer sun starts to shine brightly.

I was particularly excited this year because, in addition to the usual bounty of sporting events, Los Angeles was also hosting matches that would kick off the CONCACAF Gold Cup as well as the FIFA Club World Cup. If you love soccer, the calendar is chockablock with opportunities to watch some of the best teams show off their talents in American arenas.

But instead of combing SeatGeek for last-minute deals, I spent most of this week refreshing nytimes.com and latimes.com to track the increasing militarization of my city. While Angelenos have grown accustomed to the riot gear and overhead choppers of LAPD, watching videos of masked men in bulletproof vests and military fatigues chasing people at car washes and department stores based solely on the color of their skin was momentous even for us.

Less than six months after two infernos blazed through our hills, it seemed that the city of Los Angeles was on fire again.

A woman at a “No Kings” protest in Culver City on Saturday holds a sign with Smokey Bear issuing a warning about something other than forest fires.

At this point, you’ve likely seen the photos or the footage of Waymos on fire. Or perhaps you’ve been treated to media coverage supporting Donald Trump’s claims that there is an insurrection happening in Los Angeles (or a fact check thereof). From a distance, it probably seems like the city is under siege.

That fear, though, was not only consigned to those watching from afar. Even for me, I was nervous as I went out this week, almost expecting someone with a gun to stop me and to ask for my identification. I was on the phone with a friend who described seeing armored vehicles as she drove down the 405 highway, and my barber mentioned she had encountered tanks on Santa Monica Boulevard. The situation was anything but normal.

But as I discovered, in this, like in so many other aspects, Los Angeles is segregated. The presence of ICE is concentrated in sections of the city where the Latino population is highly represented. The National Guard seems to have focused much of its attention on the federal buildings downtown. If you were on the Westside and turned away from the news, you might not even realize the chaos that is unfolding elsewhere.

On Saturday morning, my wife and I went to the “No Kings” protest in Culver City. Hundreds upon hundreds of people marched and chanted peacefully, holding signs and Philz coffee cups as they declared that they would not stand for the violence and terror that the Trump administration was inflicting on their neighbors.

Even though the protest took place outside of Culver City Hall, just steps away from where the Culver City Police Department is headquartered, I did not see a single officer anywhere around the protest. I’m not sure if this was a strategic decision by CCPD — perhaps to keep an eye on things but to otherwise avoid any unnecessary escalation — but it certainly felt like a far cry from what had been happening downtown earlier in the week.

As a group of protestors chanted, “This is what democracy looks like,” I could not help but wonder what it was looking like in the streets of Paramount, Boyle Heights, and Elysian Park.

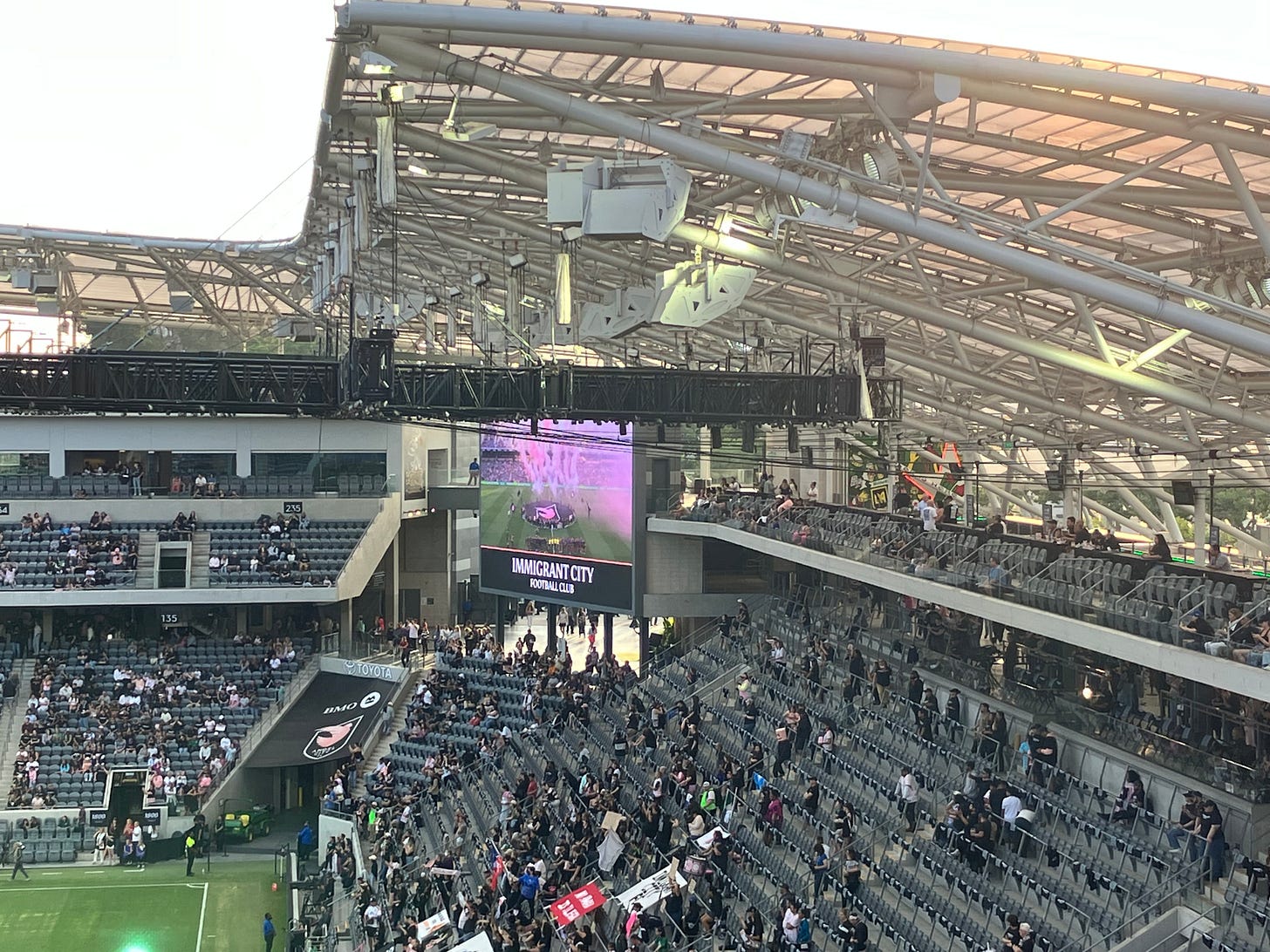

Angel City FC rebrands itself for its match against the North Carolina Courage at BMO Stadium on Saturday night.

Elysian Park is adjacent to Dodger Stadium, an arena that was originally built by displacing the mostly Mexican-American residents of Chavez Ravine. And yet, baseball’s defending champions have a large Latino fan base. The “LA” emblazoned in white on blue caps is perhaps the symbol most often associated with this city, and many immigrants proudly wear those hats on a daily or weekly basis.

But when asked this week whether they would be offering any response to the ICE raids and military activities happening around Los Angeles, the Dodgers’ chief marketing officer refused to comment. Although manager Dave Roberts has acknowledged the situation, the organization seems to want to focus fans’ attention on Shohei Ohtani racking up home runs and chasing consecutive World Series titles rather than the reality that faces so many of them once they leave the crowded Dodger Stadium parking lot to return home.

On Saturday night at BMO Stadium, Angel City FC took a different approach. The club declared itself to be “Immigrant City Football Club,” handing out black and white T-shirts declaring that “Los Angeles is for everyone” to fans as they entered BMO Stadium. The players wore the shirts, too, and as part of the pregame festivities, musician Becky G reminded those in attendance that the club itself would not exist without immigrants.

This stance is very much aligned with ACFC’s overall mission and culture. The organization proudly celebrates the diversity of its community and the city on a weekly basis, and its fanbase reflects that commitment. Even before arriving at the stadium, I knew that the team would have something planned that would present a stark contrast to the Dodgers’ cowardice.

And yet, my own feelings at the match were segregated. On one hand, I experienced the strength emanating from the supporters’ section, which declared its protest through choosing silence for vast stretches of the match, interrupting it only to proclaim “¡Chinga la migra!” or “Abolish ICE!” in the last five minutes of each half.

But on the other hand, what struck me was how empty the stadium was. Angel City FC is the league leader in attendance, averaging over 19,000 fans a match in 2024. But unfilled gray seats outnumbered fans toting pink and black jerseys by what seemed like a factor of ten to one last night. I can only offer conjecture on what kept ACFC’s typical legions away, but it’s not difficult to imagine that warnings from U.S. Customs and Border Protection that it would be present at soccer events this summer factored into some people’s decisions.

And so, in sports as in life, two different experiences emerge. Some of us get to go to soccer matches and wear our protest T-shirts, and we attend political rallies without coming face-to-face with assault rifles and riot shields. We get to stand up for what we know to be right, but we mostly do so without fear of prosecution or persecution.

But then there are those who experience the pain of this week more directly, who are disappearing, literally and figuratively, from our stadiums, our streets, and our neighborhoods. Because while Los Angeles is certainly a city of immigrants, its residents are still figuring out if it’s a city for immigrants.